How Kamala's veep picks might affect state government

Or: of course I can make this about state constitutions

President Biden’s decision on Sunday to withdraw from the presidential election, coupled with Vice President Harris’s swift ascension as the likely nominee of the Democratic Party, prompted immediate questions. Will Democrats face any legal challenges to the substitution? (No serious ones.) Will Kamala be able to take over the Biden campaign funds? (Almost assuredly.) Is Kamala constitutionally eligible to serve as President (Yes, obviously, coup-plotting lawyers’ claims notwithstanding.)

But the most important question is who will join the ticket as her running mate. Lots of names have been raised so far, including:

Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear

U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg

North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper

Arizona U.S. Senator Mark Kelly

Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker

Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro

Minnesota Governor Tim Walz

Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer

At least a few other names that were mentioned, one of which has appeared to take himself out of the running—namely, Maryland Governor Wes Moore. Another, California Governor Gavin Newsom, would pose problems under the Twelfth Amendment, because he and Harris are residents of the same state.

The selection of any of the names on that list—with the exception of Buttigieg—would have ripple effects on state-level politics, both in terms of their selection and their possible elevation to the Vice Presidency. In this post, I look at what those ripple effects would look like. (And I’ll warn you in advance—this is a long post!)

To begin, a few quick table-setting notes. Feel free to skip to the discussion of the candidates below, but I’ll refer to the context below in discussing the candidates themselves and the effects of their selection on their state governments.

Most of the likely candidates on Harris’s shortlist are governors—and there are two possible issues that could arise with the selection of a governor. First, during the campaign, the governor would be away from their state. And second, if elected, the governor would leave office.

The first problem—the governor’s absence from the state—seems like a minor issue, but it can pose some political problems. For example, Chris Christie attracted some criticism for being away from the state during his 2016 presidential campaign during a particularly nasty winter storm.

It can also pose a legal problem.

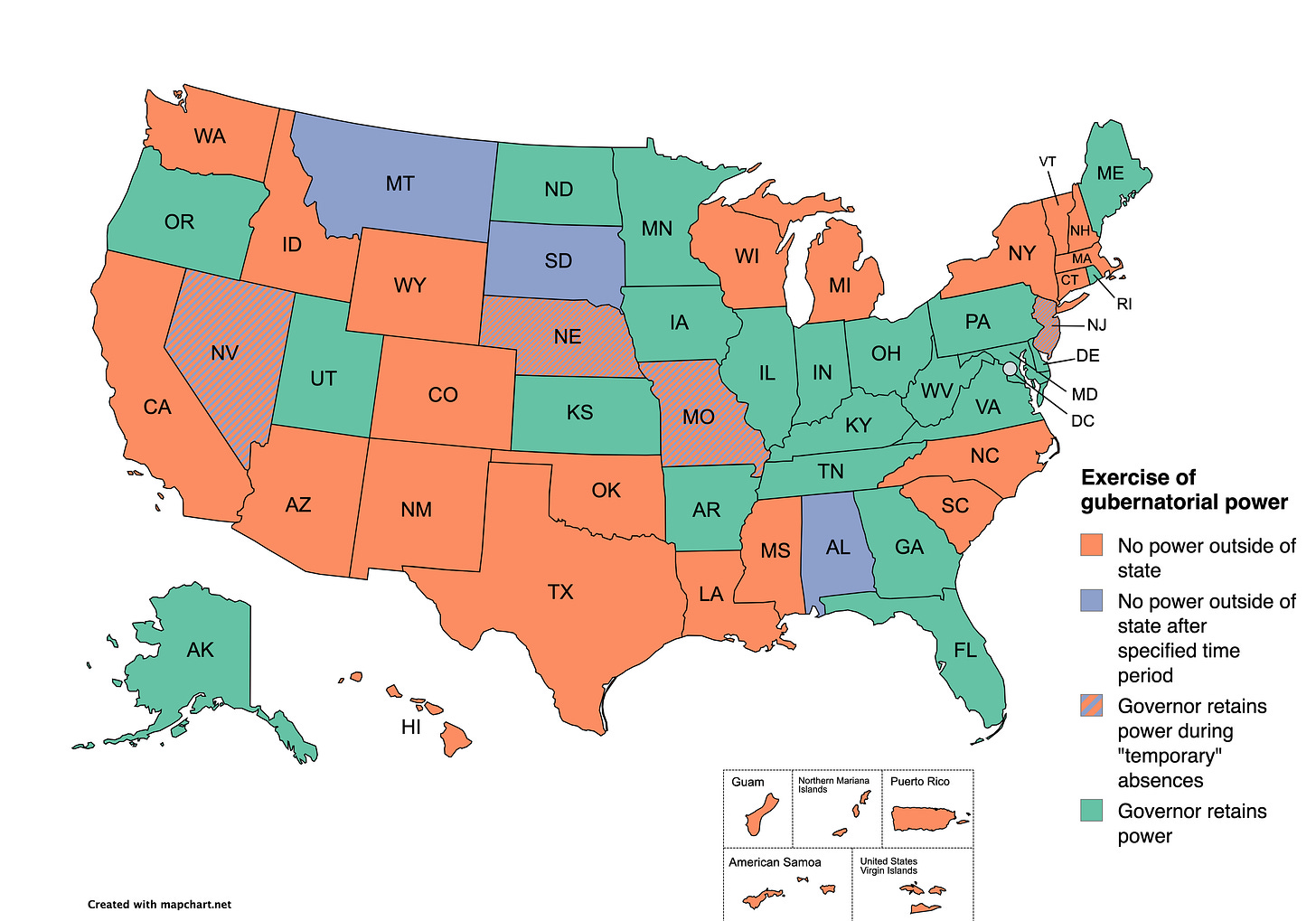

In about half of the states and territories in the United States, the governor cannot exercise power outside the state’s borders. Accordingly, upon leaving the state, power automatically (but only temporarily) transfers to their next-in-line, usually the lieutenant governor. This might sound like an odd idea, but it dates back to the nineteenth century, when a governor’s departure from their state was a much bigger deal. Over time, as states modernized their governments and adopted new constitutions (or rewrote their executive branch articles), these provisions were amended, and governors were given the power to exercise their authority when traveling. The map below shows the rules used by each state.

In most situations, this does not really pose a problem. Today, most governors are elected on a team ticket with their lieutenant governors, so even if they lost power when they popped across state lines to buy fireworks, gubernatorial power would be exercise by a member of their same party. But that isn’t the case in everywhere. Historically, governors and lieutenant governors were elected separately. It wasn’t until 1953 that New York voters ratified a constitutional amendment providing for joint election—and the first ever joint gubernatorial-lieutenant gubernatorial election then took place in 1954—that things started changing. (If this is of interest, I wrote about this history a few years ago.)

Today, most governors are succeeded by lieutenant governors who were elected on the same ticket as them (but not all are). Accordingly, whether a governor temporarily cedes power upon leaving the state, or permanently upon leaving office, there’s usually no interruption of power. Even then, however, while a governor of one party and a lieutenant governor of another is uncommon, it is certainly not unprecedented. (Historically, it happened about a quarter of the time.) And in some states, there is no lieutenant governor at all, meaning that another official (either the secretary of state or president of the state senate) is next in the line of gubernatorial succession. The map below shows how governors are succeeded in the event of any vacancy, permanent or temporary.

Even a temporary succession can cause immediate changes in governance. History is littered with examples of lieutenant governors, temporarily endowed with power as acting governor, trying to do big things while the governor is away. When Jerry Brown was serving as Governor of California and simultaneously seeking the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination, his Lieutenant Governor, Republican Mike Curb, frequently served as acting Governor and made appointments during Brown’s absence. (When challenged in court, the California Supreme Court upheld Curb’s actions.) Even when the governor and lieutenant governor are of the same party, if they’re from different factions, the same kind of dissonance can happen. In 2021, when Idaho Governor Brad Little left the state, Lieutenant Governor Janice McGeachin, a fellow Republican, attempted to issue executive orders in his absence.

Andy Beshear, the Governor of Kentucky

Beshear is in his second term as Governor—he was elected in 2019 and 2023 in close races—and is term-limited in 2027. He was elected on a joint ticket with Democrat Jacqueline Coleman in both elections, and she is still serving as Lieutenant Governor today. If Beshear were to be selected as Harris’s running mate, he’d retain his power when campaigning in other states—and if he were to win, Coleman would ascend to the governorship. While the Kentucky Constitution used to require a special election if the governor left office fewer than two years into their term, the executive branch article was totally rewritten by a 1992 constitutional amendment, and the special-election requirement was removed. Accordingly, Coleman would serve as Governor until 2027, when she’d be able to seek re-election. Coleman might experience a slight incumbency advantage, which would be helpful if she ran for re-election in the deeply conservative state.

There are a few ancillary issues that may come up. First, it’s unclear under the Kentucky Constitution if Coleman could appoint someone to fill the vacancy in the lieutenant governorship that would be caused by her ascension to the governorship. The omission of a formal procedure for appoint a lieutenant governor isn’t terribly uncommon—historically, few states had explicit procedures for filling lieutenant-gubernatorial vacancies. Informal precedent might be on her side in filling a vacancy. In 2014, when Beshear’s father, Steve Beshear, was Governor, his Lieutenant Governor, Jerry Abramson, resigned to serve in the Obama administration. The elder Beshear then appointed Crit Luallen, the former state auditor, as Abramson’s successor. Though it was unclear whether Beshear had authority to do so, Republicans in the Kentucky Legislature declined to challenge it. Whether they’d do so in Coleman’s case is unclear—the Lieutenant Governor’s power is pretty negligible—as is whether the Kentucky Supreme Court would uphold her authority.

Second, if Coleman were to win re-election in 2027, it’s somewhat unclear whether she’d be eligible to seek re-election in 2031. The most natural reading of Section 71 of the Kentucky Constitution suggests that Coleman would only be term-limited in 2035,1 but there’s no precedent for that conclusion. The text comes from the same 1992 constitutional amendment that eliminated gubernatorial special elections (as well as creating team-ticket elections), and since that time, there have been no gubernatorial vacancies. (And, of course, Kentucky Republicans have debated whether to move gubernatorial elections to even-numbered years, which would totally scramble this analysis.2)

Roy Cooper, the Governor of North Carolina

Cooper is also in his second term as Governor, but he is term-limited this year, and the state is holding its gubernatorial election simultaneously with the presidential election. So Cooper’s election as Vice President would change nothing in state politics—gubernatorial terms begin on January 1, so Cooper would be out of office when he would be sworn in as Vice President.

However, Cooper’s selection might change things in state politics—and possibly dramatically. North Carolina is one of the states that automatically transfers power to the Lieutenant Governor when the Governor leaves the state. North Carolina is also one of just two states where the Governor and their next-in-line are members of different political parties. (The other state is Vermont.) Accordingly, if Cooper were to regularly leave the state to campaign, as seems likely that he would, the Lieutenant Governor, Mark Robinson, would serve as Governor.

That could be a huge problem, given that Robinson is a far-right, Holocaust-denying ideologue—and he is also the Republican nominee for Governor this year. Cooper has had Republican lieutenant governors for both of the terms that he’s served, and he’s had virtually nonexistent relationships with both of them. He hasn’t informed them when he’s left the state, which has occasionally left each of them as acting Governor at various times without their knowledge. Earlier this year, when Cooper was out of the country, Robinson issued an executive order declaring “North Carolina Solidarity with Israel Week.” Cooper’s spokesperson criticized Robinson’s actions as a “stunt” and noted that the executive order was possibly unlawful:

“Courts across the country in states with similar constitutional provisions have held that executive succession clauses do not apply where the Governor is able to communicate and direct state business and there is no need for action by the Lieutenant Governor,” she said. “This stunt by the Lieutenant Governor and attempt to undermine our state’s democracy is harmful to North Carolina’s reputation and a reason he should never be trusted with real responsibility.”

However, only a few courts have ever been confronted with the question—and it’s unclear whether the hard-right North Carolina Supreme Court would reach the same conclusions as the courts that Cooper refers to. The stakes could also be reasonably high. While Republicans in North Carolina have a legislative supermajority and can pass bills over Cooper’s veto, governors have other powers. If a judicial vacancy occurred while Cooper was out of the state, Robinson could fill it without any requirement of a confirmation vote. To that end, Republican judges facing mandatory retirement could strategically resign while Robinson was acting governor to avoid being replaced by Cooper (or Josh Stein, the Democratic nominee for governor). Robinson could also do more than issue executive orders—he could also fire Cooper’s appointees who head state departments. There’s a lot of chaos that could unfold!

Moreover, just because Robinson hasn’t done this yet doesn’t mean that he wouldn’t. In an interview with WRAL, he expressed both skepticism about exercising power as acting governor and a willingness to do so under the right circumstances:

“I would hate to have to make a law for common courtesy and for common professionalism, but it’s a possibility,” Robinson said. “We’d have to sit down and review and make sure that it would be a law that would be effective.”

In the same WRAL interview, the lieutenant governor expressed both an openness and reluctance to taking action when the governor is out of town.

“There is no way that I would take a chance of doing something of that nature just to take a pot-shot at somebody,” Robinson said. “That would be cheap and beneath this office.”

One minute later, however, he added: “It would depend on the length of time and what was going on at that particular moment. I’ll just leave it at that and what was going on at that particular moment. We would play it by year and we would be completely fair and open and honest about anything that we would do.”

What Robinson might do in such a situation is certainly unclear—but he’s unpredictable.

Mark Kelly, United States Senator from Arizona

Mark Kelly is in his second term in the U.S. Senate and his first full term. He was first elected in a 2020 special election, defeating Republican Martha McSally, who had been appointed to the Senate following John McCain’s death. Kelly was then re-elected in 2022 to a full six-year term.

If Kelly were to be selected as Harris’s running mate, the effects would be felt most acutely in what the U.S. Senate could do. Democrats have a thin 51-49 majority in the Senate, and Kelly’s absence would functionally reduce that to a 50-49 majority. Given Democratic-turned-independent Senator Joe Manchin’s one-man crusade against any Biden judicial nominee who lacks Republican support, Kelly’s absence could compound Democrats’ existing difficulties to confirm Biden’s more controversial nominees. (Because Harris won’t be around to break ties.)

If Kelly were to be elected, he would resign his Senate seat and Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs would appoint his replacement. Hobbs is a Democrat, so there’s no risk of Kelly’s vacancy causing his seat to flip—but even if she weren’t, state law requires that the Governor make a same-party appointment in filling any U.S. Senate vacancy. However, the vacancy would require that a 2026 special election be held to fill the remaining two years of Kelly’s original term. While Arizona is trending blue, the prospect of defending another seat in what could be a challenging 2026 midterm could be daunting.

J.B. Pritzker, the Governor of Illinois

Pritzker is in his second term as Governor, and unlike most governors, he isn’t term-limited—he could seek re-election in 2026 and beyond. Like Beshear, Pritzker would be able to exercise power outside the state, but it wouldn’t much matter anyway, because he would be succeeded by his Lieutenant Governor, Juliana Stratton, a fellow Democrat. If Pritzker were to be elected and Stratton were to become Governor, she would become the first Black woman to ever serve as a state governor.

Unlike in Kentucky, where it seems plausible that a lieutenant-gubernatorial vacancy could be filled by the Governor, any such vacancy in Illinois would remain unfilled. Rather oddly, the state constitution provides: “If the Lieutenant Governor fails to qualify or if his office becomes vacant, it shall remain vacant until the end of the term.” In that case, Attorney General Kwame Raoul would be next in line for the governorship.

Otherwise, there are comparatively few effects that would be felt in Illinois. The absence of a lieutenant governor, while disruptive to the line of succession, would have few other effects. In other states, the lieutenant governor serves as the president of the state senate and breaks ties, but that isn’t the case in Illinois. If Stratton were to run for re-election in 2026, she’d pick a running mate at that point—and would likely win, given Illinois’s status as a reliably blue state—and would fill the lieutenant-gubernatorial vacancy at that point. She, like Pritzker, would be able to run for re-election as many times as she wanted.

Josh Shapiro, the Governor of Pennsylvania

Shapiro is not even two years in to his first term as Governor. He was elected in 2022, the first time since 1844 that Democrats won three successive gubernatorial elections in the state. Shapiro, like Beshear and Pritzker, has a fellow Democrat serving as Lieutenant Governor—Austin Davis—and would be able to exercise his power outside of the state. Unlike them, however, Shapiro didn’t pick Davis; they were nominated in separate primaries and then appeared on the same ticket in the general election.

In Pennsylvania, the downstream effects of Shapiro’s possible election as Vice President are somewhat more attenuated—but quite significant. If Shapiro were to leave office, Davis would become Governor. Though Davis could run for re-election in 2026, it’s unclear whether he could seek re-election in 2030, but based on the text of the relevant constitutional provision, I’d think not.

Davis would have no power to fill the vacancy caused by his own ascension to the governorship, however, because under the Pennsylvania Constitution, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate automatically becomes Lieutenant Governor—while simultaneously continuing to serve as President.

That could actually prove to be quite logistically difficult. Democrats are hopeful that they might be able to win a majority in the State Senate for the first time in decades, either by winning three seats to tie the chamber or four seats to win an outright majority. And therein lies the difficulty, because a three-seat gain is far likelier than a four-seat gain. If Democrats were to gain three seats and tie the chamber, 25-25, they could rely on the Lieutenant Governor’s constitutional power to break ties to elect a Senate President of their choice. Their majority would be limited in many meaningful ways—they could not pass a bill or constitutional amendment with the Lieutenant Governor’s tie-breaking vote, for example, both of which are pretty big deals.

If, however, Davis becomes Governor, he wouldn’t be able to break ties in the Senate, and it’s not super clear how the Senate would be organized. If the chamber is tied, 25-25, there would be no official method of breaking the tie. As such, the parties would need to come to some kind of agreement—which is certainly not without precedent—as to who would serve as Senate President Pro Tempore and as Lieutenant Governor. As a practical matter, it would very likely eliminate any chance of Democrats winning a trifecta in Pennsylvania.

Tim Walz, the Governor of Minnesota

Walz is in the middle of his second term as Governor and, like Pritzker, faces no term limits, so he could run for re-election in 2026 and beyond. He would hold onto his power upon leaving the state, and would be succeeded as Governor by his Lieutenant Governor, Peggy Flanagan—who would become the first Native American woman to serve as governor of any state.

Like with Shapiro, Walz’s election could pose challenges, but is substantially less likely to do so. The Minnesota State Senate is currently tied, 33-33, with one vacancy. Because the vacancy took place after the legislative session ended, Democrats enjoy a technical majority. The Senate is not up this year, but there is a special election to fill the vacancy in Senate District 45. The district voted for both Biden in 2020 and Walz in 2022 by double-digits, but Republicans have said that they’ll target it.

Why does any of this matter? Because in Minnesota, the President of the State Senate succeeds to the lieutenant governorship upon a vacancy. If Republicans win the special election, they’d win a 34-33 majority in the State Senate, and could elect a State Senate President. Then, upon Walz’s resignation as Governor, that Senate President would become Lieutenant Governor.

There are ways around this, though. If Harris-Walz is the ticket and they win the election, but Republicans flip SD-45, Walz could resign as Governor early to allow the current Senate President, Democrat Bobby Joe Champion, to become Lieutenant Governor. Then, the subsequent Republican majority in the State Senate would not cause a party switch in the lieutenant governorship.

Probably, anyway. To me, that’s the best way to read the Minnesota Constitution, which provides: “The last elected presiding officer of the senate shall become lieutenant governor in case a vacancy occurs in that office.” That language—“shall become”—is pretty significant, because it clearly indicates that the Senate President is not merely acting as Lieutenant Governor, but rather becomes Lieutenant Governor. Consider the effect if the Senate President were merely acting as Lieutenant Governor. If that were the case, then the election of a new Senate President would rather naturally result in a new acting Lieutenant Governor.

Recent precedent, though admittedly not any judicial decisions, supports this reading. In 2018, when then-Governor Mark Dayton appointed Lieutenant Governor Tina Smith to the United States Senate to succeed Al Franken, Republican Michelle Fischbach, then the Senate President, became Lieutenant Governor. Fischbach held onto her Senate seat, and her presidency, which caused some controversy. To avoid a small constitutional kerfuffle—specifically, questions as to whether she could permissibly hold both roles—Fischbach ended up resigning her Senate seat. She remained as Lieutenant Governor without any challenge.

Of course, all of this is irrelevant if Democrats were to win the SD-45 special election. In that case, they’d hold onto their 34-33 majority in the State Senate, a Democrat would succeed Flanagan as Lieutenant Governor, and a special election would have to be held to replace whomever that is.

Gretchen Whitmer, the Governor of Michigan

Whitmer is also in the middle of her second term, and is term-limited in 2026. Though she, like Cooper, cedes her power as governor upon leaving the state, it passes to her Lieutenant Governor, Garlin Gilchrist, her running mate from the 2018 and 2022 elections. Accordingly, if Whitmer were to be elected Vice President, Gilchrist would become Governor for the remainder of the term.

What happens next is a little bit of a mystery. Though there is a law on the books in Michigan that allows the Governor to fill a lieutenant-gubernatorial vacancy, on two separate occasions, the Attorney General of Michigan has issued an opinion that it is unconstitutional. There haven’t been any vacancies that have triggered the law, so the outcome here is unclear.

However, it isn’t likely that this will matter. Democrats currently have a 20-18 majority in the Michigan State Senate, and the Lieutenant Governor serves as the Senate President, with the power to break ties. Control of the State Senate is not up this year—it’s next up in 2026—so the risk is really that an untimely vacancy, coupled with a Republican pickup in an ensuing special election, could plausibly tie the chamber. How the Michigan Supreme Court would interpret the state constitution—which does not speak to the question at all—is unclear, especially given that control of the court is on the line with this year’s elections.

Gilchrist would be able to run for re-election in 2026 and 2030—potentially allowing him to serve from 2025-2035. The Michigan Constitution phrases the applicable term limit here kind of awkwardly,3 but given that Gilchrist would be serving less than half of a single term if he succeeded Whitmer (her term began on January 1, 2023, and her hypothetical term as Vice President would begin on January 20, 2025), the term wouldn’t count for purposes of the term limit.

All of this is to say that, regardless of whomever Kamala Harris eventually picks as her running mate, there could be ripple effects both during the campaign and in the event of her victory. I think that some of these effects are more serious to consider than others, but even then, if Kamala is persuaded that one of them would offer a serious electoral advantage, any of those effects are clearly subordinate to the benefit they’d confer.

Specifically, Section 71 says: “The Governor shall be ineligible for the succeeding four years after the expiration of any second consecutive term for which he shall have been elected.” I read “for which he shall have been elected” as modifying “second consecutive term” such that it refers to a second elected term, but it’s possible to read it so that the ineligibility attaches upon the start of the second term, regardless of whether the first term occurred by succession or election.

If you care for the full explanation, the proposal (which didn’t make it onto the ballot this year as a constitutional amendment) would provide for the election of the Governor in 2027 for a five-year term, which would expire in 2032, and then there would be four-year terms after that. If that amendment were, at some point, to be ratified, Coleman might be eligible to be elected in 2027 and again in 2032, meaning that she could plausibly serve as Governor from 2025-2037!

The text says: “Any person appointed or elected to fill a vacancy in the office of governor, lieutenant governor, secretary of state or attorney general for a period greater than one half of a term of such office, shall be considered to have been elected to serve one time in that office for purposes of this section.” But it would be odd to say that Gilchrist, by virtue of being lieutenant governor, was appointed to fill a vacancy in the office of governor. Nevertheless, that feels like the most natural way to read the statute. (It also implies that Gilchrist could appoint a lieutenant governor.)