The disappearance of elected public utility commissions

Whether this ensures the selection of highly qualified utility regulators or stymies voters' ability to push for action on climate change and environmental justice is debated

In 2020, New Mexico voters ratified a constitutional amendment that converted the state’s elected Public Regulation Commission into an appointed body. The Commission, which regulates public utilities, has a long history in New Mexico politics—dating back to the state’s original constitution, adopted in 1911, which created a Corporation Commission. The original Corporation Commission consisted of three members elected in statewide elections to six-year terms, but a 1996 constitutional amendment reorganized the Corporation Commission into the PRC. The amendment also added two new members, and converted the board’s selection mechanism from statewide election to election by district.

The election of the PRC by district meant that New Mexico’s racial and ethnic diversity would be reflected in the regulation of the state’s public utilities. In every redistricting cycle since the PRC was established, a Native-majority district was drawn in the northern part of the state. In 1998, when Democrat Lynda Lovejoy was elected to the PRC, she became the first Native American to serve on any state’s public utility commission. Since Lovejoy’s election, District 4 on the PRC has been represented by Native commissioners.

Accordingly, when New Mexicans ratified a constitutional amendment converted the PRC from an elected body into a smaller commission appointed by the Governor, several Native groups filed suit against it. They argued that depriving the state’s Native communities of the ability to elect a member of the PRC, and the insulation of the PRC from voter input, would shift the PRC’s regulatory balance toward favoring energy companies—and away from protecting indigenous lands. Their legal challenge focused on an argument that the amendment violated the state constitution’s subject-matter requirements. In the end, the New Mexico Supreme Court unanimously rejected the groups’ challenge to the amendment.

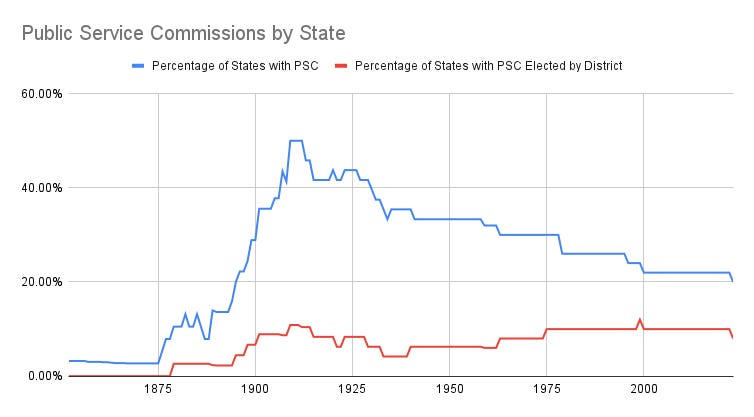

While the process of converting the state’s public utility commission from an elected to an appointed body was unusually contentious in New Mexico, the removal of public utility commissioners from the ballot has been fairly commonplace in the United States over the last century. While the public utility commissioner was once a fairly common office for voters to see on their ballots, most of the states that once had elected PUCs have abolished them—or converted them to appointed bodies.

Most public utility commissions were first created as railroad commissions. The history of railroad commissions is long, complex, and almost always state-specific—but the quick and dirty explanation is that, owing to the largely ineffective state regulation of railroads in the mid-to-late 1800s, many states experimented with creating separate bodies to specifically regulate railroads. Across the country, state legislatures took wildly different approaches, disagreeing vigorously on whether the railroad commissions should be elected (democracy!) or appointed (merit!), what powers they should have, and how to safeguard their independence.

In states where railroad commissions were created statutorily, as opposed to constitutionally—which was most of them—changes here were quick and jarring. Minnesota established an elected Railroad Commissioner in 1875, abolished the office in 1885, and resurrected it in 1899 as a three-member body. Tennessee created a three-member Railroad Commission in 1883, its members were elected in 1884, and the legislature abolished it in 1885, just several months into the commissioners’ terms.

The trend was clearly in favor of election as the nineteenth century ended and the twentieth century began, however. Most states opting for the electoral approach created multimember railroad commissions with staggered terms.

Beginning in early 1900s, however, the number of companies in need of regulation—in need from the vantage point of progressive state legislators, anyway—grew. Some of these companies, like those involved in electricity generation and distribution, telecommunications, and water services, looked superficially a lot like railroads. To provide services to their customers, these companies needed to create complex, grid-line distribution systems requiring high investment costs, and customers may have little choice in what service provider they have.

As a result, two governors—Charles Evans Hughes of New York and Robert La Follette of Wisconsin—pushed for the creation of public service commissions to regulate all of these companies as public utilities. The easiest way to do this was to expand the jurisdiction and regulatory authority of railroad commissions, which already regulated railroads as public utilities.

At the same time, La Follette urged that Wisconsin create a gubernatorially appointed commission. He argued that elections, while providing the public with input into the selection of the commissioners and the direction of its regulation, ultimately allowed for greater corporate influence:

The encroachment of the great railway systems, allied with industrial trusts and combinations, upon democracy, is a constant menace to whatever degree we may perfect the laws providing for the machinery of popular government. Every additional temptation for these great organizations as a system to take part in the elections, should be removed. Surely it is the part of wisdom to add none unnecessarily.

He argued that, given the increasing complexity of public utility regulation, having gubernatorially appointed commissioners would ensure more qualified regulators while also safeguarding the public’s opportunity to scrutinize the candidates:

On the other hand, if the office is made appointive, there will be every opportunity for the appointing power to make selection from the widest possible field, having ample time for investigation of the candidate with respect to his antecedents, to the elements in his character, and to his ability, experience, and expert knowledge. The selection would be made full in the eye of the public, the appointing power having responsibility for his acts, and knowing with a certainty that such appointment would not be confirmed unless it met the approving judgment of the legislature.

The Hughes-La Follette approach proved wildly popular. Many governors across the country urged their state legislatures to embrace it—by both expanding their states’ existing railroad commissions and by making them appointed bodies. In doing so, these governors parroted La Follette’s arguments verbatim and expressly couched their recommendations in the argument that what they were suggesting was materially identical to what was being done in New York and Wisconsin. Though states continued to create elected commissions—when Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma joined the Union, they each entered with elected corporation commissions, for example—in the next few decades, the percentage of states with elected railroad commissions or PUCs plummeted. In 1912, 50% of states had elected public utility commissions—and since then, it’s been a steady decline, and today, just 20% of states do. New Mexico is the most recent state to remove its PUC from the ballot, but Kentucky did so in 2000, Tennessee in 1996, and Florida in 1978.

However, for the most part, PUCs that are elected by district, as opposed to statewide, have proven far more durable. California was the first state to provide for a commission elected by district, which it did in its 1879 Constitution, and though the California Railroad Commission was abolished in 1911, several states adopted a similar approach:

Kentucky, in its 1891 Constitution, created a three-member Railroad Commission elected by district that existed until 2000

Louisiana, in its 1898 Constitution, created a three-member Railroad, Express, Telephone, Telegraph, Steamboat and Other Water Craft, and Sleeping Car Commission (later converted into the Public Service Commission) elected by district; it was continued in the 1913, 1921, and 1974 constitutions and expanded to 5 members in the 1974 constitution

Oregon briefly created a three-member Railroad Commission in 1907, which was converted into the Public Service Commission shortly thereafter; it had two members elected by district and one member elected statewide and was abolished in 1927

Mississippi converted its statewide elected Public Service Commission to one elected by district in 1938, Nebraska did the same in 1962, Montana in 1974, and New Mexico in 1996

(If you’re interested in reading about how states have redistricted their public service commissions—as well as similar bodies like state boards of education—I have an article, Shadow Districts, that will be published with the Cardozo Law Review this year on that exact topic, currently available on SSRN.)

Today, 11 states—Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Texas—continue to elect public utility commissions, though the names, terms, and details all vary.

For the most part, debates over PUCs’ continued existence as elected bodies are quiet. Perhaps we’re unlikely to see significant changes to the makeup of state democracies in the immediate future—in an era of extremely high political polarization, any changes might be seen as having partisan motivations. On the other hand, we’re seeing significant changes in how state elections are conducted, and perhaps this will trickle down at some point into which offices are elected.

Several ongoing controversies could help push things in a different direction. In Georgia, the usage of statewide elections to pick members of the Public Service Commission has been challenged as a violation of the Voting Rights Act, with plaintiffs arguing that districts should be used to ensure adequate representation of Georgia’s Black voters. In Mississippi, the state’s supreme court districts—which are used to elect the Mississippi Supreme Court, Public Service Commission, and Transportation Commission—are being challenged in court, both because they haven’t been redrawn since 1987 and because they discriminate against Black voters. And in Montana, after decades of not redrawing the boundaries for the state Public Service Commission districts, the state legislature drew a brutal Republican gerrymander—which could face a legal challenge. The outcome of these lawsuits could shape how these bodies are elected.

Personally, despite an academic interest in how these bodies are selected, I’m not sure I have a strong opinion myself. On one hand, public utility law is extremely complicated and highly technical—and I am quite skeptical that partisan elections will produce highly qualified utility regulators. On the other hand, making utility regulators directly accountable to the public may help—in some states, anyway—push for better action to combat climate change and environmental racism.

But, in any event, we shouldn’t treat the method of selection for any office as settled and beyond debate. Though it’s repeated ad nauseum that states are “laboratories of democracy,” if that’s really true, then we should all take our responsibilities as junior democratic scientists seriously—and constantly question why we’re doing what we’re doing.